From the vault: The Death of Jimmy Garcia.

This article is an abridged and updated version of a story included in my book The Soul of Boxing. (HarperCollins, 1998) - longlisted for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year award.

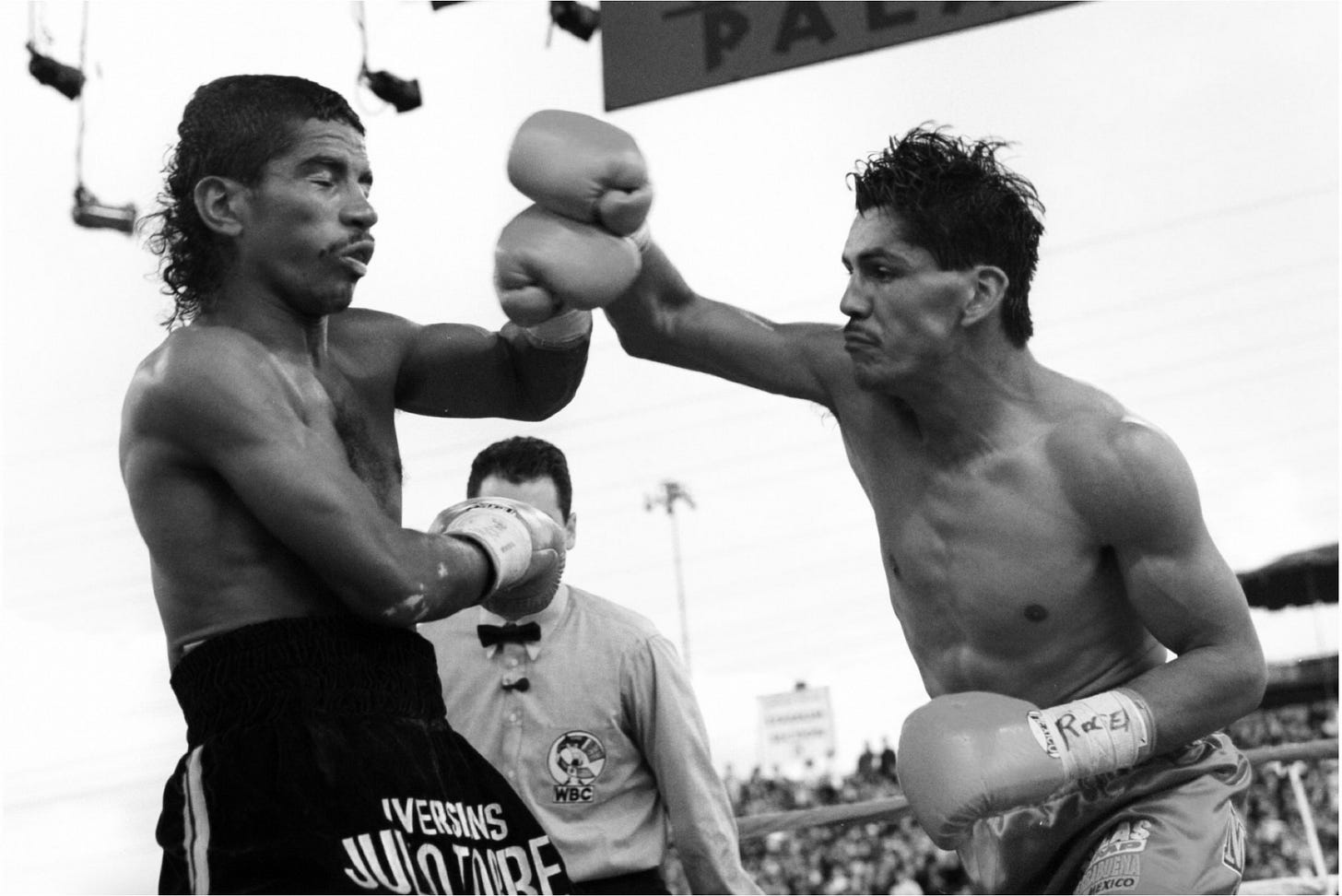

Jimmy Garcia, left, versus Gabriel Ruelas in 1995. Garcia would later die because of brain injuries. (Tony Duffy / Getty Images Sport)

Sometime back in the late 90's, shortly before I started writing The Soul of Boxing, the American writer Leigh Montville wrote, In Sports Illustrated magazine, "Super featherweight Jimmy Garcia, the Colombian boxer, could not worry about danger. He described himself as a prince. He said he was ''born to box. I'm not going to live long,'' he used to say. ''Maybe 30 or 35 years. The lives of princes are short like that. And I am a prince of sport. There's no doubt about it, so there's no reason to fear death.'' He had a 35-4 record. He had never been knocked out and had been knocked down only once. He had two daughters and a common-law wife. His friends said he had a photographic memory. He read Gabriel Garcia Marquez. He read Edgar Allan Poe. He had plans to go to college after he won a world championship. And then he fought Gabriel Ruelas, suffered a brain injury and died. He was 22."

A few years earlier, just before Christmas 1991 Garcia, still a teenager, lay on his bed in the dead of night and dreamed about boxing. He was stepping onto a canvas enclosed by ropes, wearing little but shorts shoes and gloves. He danced and skipped, shadowboxing around the edge of the ring. He could see his opponent but something was wrong. The other fighter lay still on the canvas, stretched out across the centre of the ring, body contorted, neck twisted. "Get up, get up," Jimmy shouted, "the fight hasn't started yet. Come on, come on, what are you waiting for?" There was no reply.

Jimmy stood still, gently tapping his gloves together. He looked at the body on the canvas and then suddenly the ring started to spin and tilt and Jimmy fell backwards into the ropes. His arms were caught and as he tried to free himself the other boxer began to move towards him. Jimmy watched the corpse slide down the canvass slope and he screamed as it slipped in between his scrambling legs and underneath the bottom rope into oblivion.

He woke up in a cold sweat from the fear. "Jesus," he whispered, "sweet Jesus," and sat up on the edge of the bed. He closed his eyes and remembered the face of the dead boxer. The face was his own face. He shivered at the macabre thought, but as the memory came flooding back, Jimmy Garcia just shook his head. 'Strange,' he whispered and went back to sleep.

Jimmy Garcia died of brain damage after trying his heart out to win a pitiless but deeply moving encounter; a violent ritual of conflict that he believed to be not only justifiable as a sport and necessary as a way to make a living, but even more superior to life itself. Unlike life, boxing contains nothing that is not fully willed. Garcia willed to win at all costs and paid the highest price of all, and yet, like boxing's countless other victims, could he somehow return to talk about his fate he would not condemn the profession of violence that ended his life so prematurely and with such savage force. Instead, Garcia, killed as a result of suffering repeated blows to the skull, would speak passionately about the soul of boxing and how it should be compared to life and not death.

Carmen Garcia often talks about destiny. Hours after her son's dramatic funeral, when his casket rode atop a blaring fire engine - Jimmy Garcia had said he would celebrate the greatest victory of his career with a fire-engine ride through his home town - Carmen was asked if she regretted not doing more to prevent Jimmy from pursuing a career in boxing. "No," she replied, "it was his calling in life. His great love. I think he was destined to die a hero pursuing his dream.

"I have prayed and prayed to God to try and make sense of what has happened," she said, trying to hold back the tears in the company of her five remaining children. "I don't resent boxing. I'm just in pain. It is the mother who suffers the most. I lost the most important thing in my life, after God, and now boxing makes no sense to me. But these are matters of destiny."

Jimmy Garcia believed in God and prayed before a fight, but his faith in personal beliefs is not unique, in fact, it is commonplace in a profession whose currency is blood and sometimes death. It is though the absolute base destructiveness of boxing, the will to destroy a life, that puts a man in touch with his soul in such an intense way that his spirituality is awakened. In this strange way, boxing is like no other sport, if it can be called a sport at all, because in no other single group of athletes are there so many who profess faith in personal beliefs. Perhaps the greatest irony of all is the absence of nihilism in boxing.

'At its moments of great intensity, it(boxing) seems to contain so complete and powerful an image of life - life's beauty, vulnerability, despair, incalculable and often self-destructive courage - that boxing is life, and hardly a mere game,' wrote American novelist Joyce Carol Oates. 'During a boxing match we are deeply moved by the body's communion with itself by way of another's intransigent flesh. The body's dialogue with its shadow-self - or Death. Considered in the abstract the boxing ring is an altar of sorts, one of those legendary spaces where the laws of a nation are suspended: inside the ropes, during an officially regulated three-minute round, a man may be killed at his opponent's hands but he cannot be legally murdered. Boxing inhabits a sacred space predating civilization; or, to use D.H. Lawrence's phrase, before God was love. The boxing match is the very image, the more terrifying for being so stylized, of mankind's collective aggression; it's ongoing historical madness.'

Somewhere between the time of Jimmy Garcia's death and his funeral, I made up my mind to investigate the compelling irony of the so-called 'god-fearing-fighter'. For years, as a sportswriter, I had cheated the truth about the biggest contradiction in the history of the sport, but suddenly I was left with little choice but to test the seemingly unbreakable link between religion and the darkest of trades. It was the least I could do for Jimmy Garcia who, in life, fuelled my passion for boxing with his intoxicating courage and skill, but in death made me feel sick to my stomach with guilt and shame for allowing myself to feel excited when a man begins to seriously bleed.

Donald McRae, the immensely gifted South African writer, best summed up this feeling of voyeuristic hypocrisy in his book Dark Trade: 'I did not think of myself thirsting for gore but accepted the basic ferocity of boxing. I think it captivated me. I hated violence outside the ring but, between those thickly knotted ropes, the brutality became expert rather than malicious, a force of terrible grace when a fighter welded his power to boxing's most ancient finesse. It was a lie. The feelings of beauty only came later, in black and white photographs which sucked out the ravaging malice and ugliness of any given moment in the ring and turned them into stunning, and stunned reflections of emotion. I gave into the silent deceit because it helped me go on, it enabled me to take another fix, allowing me to drum up another dodgy metaphor to report how one man knocks another unconscious.'

Gabriel Ruelas, the Mexican who killed Jimmy Garcia, had a theory about God and boxing and why 'Christian fighters' can and do exist in the sport's shadowy world. Ruelas' dreams of death grew so vivid after Garcia lost his fight for life that he could not sleep. In the end, he came to this conclusion: "It is not God's will that men should deliberately try to hurt each other. The ring is a place devoid of God's grace and mercy."

For Ruelas, Garcia's death was the saddest of ironies. Ever since he was a child, both asleep and awake, Ruelas had been envisioning his imminent death; sometimes a plane crash, or a car wreck, sometimes he's not sure how it happened; he's just floating near the ceiling, gazing down upon his corpse. As Garcia lay comatose in a Las Vegas hospital Ruelas had a terrible thought: 'If I have been wrong all along - if I am the executioner, not the victim, then, God, everything's screwed up.'

Maybe everything is screwed up in the pursuit of such a brutal kind of stardom, but Garcia is one of the sanest people I have ever met and he spoke with a strong, sobering conviction. "A fighter's goal is a knockout. That is concussion which is an injury suffered by the brain when it is caused to slap up against the bone of the skull. Of course, most, if not all, fighters have no wish to cause such an injury, but we will, to win."

The brain is, therefore, a casualty of war, in the ring. The brain is traumatized; in shock, it cannot function and done with enough force injury goes beyond just bruising. The best fighters deliver blows that cause the brain to slap the skull bone so hard as to rip the brain's tissue and its blood vessels. In which case the brain bleeds. Jimmy Garcia's brain became a river of blood.

He died in the early hours of Friday, 19 May 1995. He lost his life trying to win a green belt in a fight for which he was due to be paid $20,000. Ruelas, the champion, had been promised $300,000 and he would have sacrificed every last penny to see Garcia live. They operated on Garcia's brain thirty-five minutes after Ruelas's last punch. At the University Medical Centre in Las Vegas surgery to remove a one-inch blood clot - a subdural hematoma - took two hours to complete.

For five long days Garcia clung by the faintest of threads to the black rim of death surrounding his expiring life. Ruelas was at his bedside, praying with the Garcia family. On Wednesday, 17 May 1995, Ruelas was approached by the pastor of a church who said: "Gabriel, God does not blame you for this. Jimmy Garcia's blood is not on your hands. You are innocent; there is no condemnation."

Ruelas wanted to believe him, but could not. They switched off the life-support machine at 1.43 am that Friday morning; and when Ruelas heard the news he felt like dying. Twenty-four hours earlier he had been praying to God for a miracle but the coma only deepened. Ruelas was distraught and for what seemed like an eternity vivid memories of the pre-fight press conference at Caesars raged in his mind.

"I have trained very hard for this fight and I haven't seen my son for seven weeks," he told journalists, "so somebody will have to pay for that. Jimmy Garcia will have to pay for it." It was more than hype because Ruelas hated being away from his family and every time this happened he would make his opponent the focus of his resentment. Instead of blaming himself for living such a destructive way of life, he blamed the man he was about to fight and right now Jimmy Garcia had cost him countless hours of loneliness. "I'm certainly going to make him pay for it," he said in harsh words that would come back to haunt him.

"Please forgive me for saying that, I deeply regret it," he told Garcia's father Manuel. "I had to make peace with Jimmy's family and they were very gracious. They said they did not blame me; that God did not blame me; that Jimmy had gone to be with Jesus and that he didn't blame me. But Mrs Garcia kept staring at my hands and said she was looking at 'the hands that killed my son.' Even so, she said she did not hold me responsible and said that whenever she sees me fighting on TV, she will see Jimmy and pray for me."

But Ruelas does not believe that God answers prayers for boxers. "When you step into the ring," he said, "you are in conflict with Christianity. In the Bible, it says 'thou shalt not kill,' and while no boxer wants to seriously injure or kill his opponent the harsh truth is he is prepared to take a life. There are no excuses because a boxer is aware of the possible consequences of his actions in the ring and accepts it as part of his job. Many boxers have a strong faith in personal beliefs but I wonder how many have no conflict inside and how many can honestly say they are doing what God wants them to do?"

Maybe Ruelas is right. Perhaps God frowns on the great dark prince of sports. In December 1995, seven months after killing Garcia, Ruelas was back in the ring, fighting the African great Azumah Nelson. As Nelson’s fierce punches dropped Ruelas to the canvas in the fourth round of the bout in the Southern California desert that night, Ruelas looked skyward and saw a second, familiar man standing over him, wearing an expression of delight. It was the ghost of Jimmy Garcia.